Americans living in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not commonly travel unless absolutely necessary because it was usually difficult, costly, and could even be quite dangerous. Most travelers were free white men who journeyed for important business reasons, but sometimes enslaved African Americans were given special permission to travel to conduct business on behalf of their owners. For those who did travel, inns and taverns provided overnight accommodation, food, and drink for both people and horses. After the American Revolution, road networks expanded, and the number of taverns and inns soared to accommodate the needs of increasing numbers of travelers.

One of the most practical and fastest ways to travel, especially in and around the Chesapeake Bay region, was by water. Entrepreneur Horatio Middleton opened a tavern in Annapolis in 1750 as a sideline to the ferry he operated running back and forth to the Eastern Shore. Of course, not everyone had access to waterways or funds to pay for traveling by boat. The poor had no choice but to walk; those with some spare funds may have traveled by horse; and the wealthiest used coaches pulled by horses and driven by coachmen. The earliest roads available to settlers were trade routes established by local American Indians that had been widened to accommodate large wagons. By the early eighteenth century, more formal road networks developed and in 1699 and 1704 Maryland’s General Assembly enacted provisions to provide directional signage on them using notches in trees. This three-notch system was first used in Prince George’s, Baltimore County, and St. Mary’s Counties. People understood that one notch on a tree indicated the way to a church, two notches pointed to a courthouse, and three notches led to a ferry.

Once the American Revolution was over, road building became a priority and the first major highway, the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, was chartered in Pennsylvania in 1792. Then, to encourage settlement of the newly opened Ohio Valley, the Federal Government passed legislation in 1806 funding construction of the National Road. Upon its completion in 1834, this 620 mile-long highway stretched from Cumberland, Maryland to Illinois, and in doing so crossed over the Cumberland Mountains and snaked through Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana.

To accommodate the growing number of travelers, many taverns and inns were established offering sleeping accommodations, food, and drink. In addition, taverns also became community centers used for business meetings, mail distribution, political campaigning, places to hold sales and auctions, and became sites where itinerant dentists, doctors and barbers set up shop, among other uses. Cleanliness of the sleeping spaces and the quality of the food and drink varied greatly from one tavern to another. In 1765, a visitor to the Eastern Shore of Virginia stayed at a tavern that offered “nothing for Man or horse but Stinking Rum and as bad Wine no meat and little bread ground at a hand mill and backed in a dirty manner at the fire [sic].” In contrast, Mann’s Tavern in Annapolis was known for its elegance and top-rate food and wine. In 1783, Mann’s was engaged by Thomas Jefferson as the venue for a celebration in honor of George Washington upon his resignation from the army, an event attended by over 200 dignitaries who consumed $644 worth of Mann’s fine wines. Most middle of the road (pun intended) taverns offered plain but decent food that was simply prepared and locally sourced. The description of a dinner served at City Coffee House in New London, Connecticut in 1790 offers a good example of a typical early American tavern experience:

At about two o’clock they dine without soup. Their dinner consists of broth, with a main dish of an English roast surrounded by potatoes. Following that are boiled green peas, on which they put butter which the heat melts, or a spicy sauce, then baked or fried eggs, boiled or fresh fish, salad, which may be thinly sliced cabbage seasoned to each man’s taste on his own plate, pastries, sweets to which they are excessively partial and which are insufficiently cooked. For dessert, they have a little fruit, some cheese and a pudding.’

Similarly, most taverns served locally sourced low-cost beverages such as ale, cider, peach brandy, punch, rum, and perhaps some higher priced fortified wines or spirits. Though not necessarily still serving foods and drink popular in the past, many taverns established hundreds of years ago in the Chesapeake region are open for business today. Hit the road and immerse yourself in the ambience of a centuries’ old Chesapeake tavern today.

Joyce White, a food historian, can be contacted through www.atasteofhistory.net.

Historic taverns

c. 1750 Middleton Tavern, Annapolis

2 Market Space, Annapolis, MD 21401; 410-263-3323

Horatio Middleton opened this establishment as an Inn for Seafaring Men in 1750 to accommodate passengers who used his ferry linking Annapolis to the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

c. 1747 Reynolds Tavern, Annapolis, MD

7 Church Circle, Annapolis, MD 21401; 410-295-9555

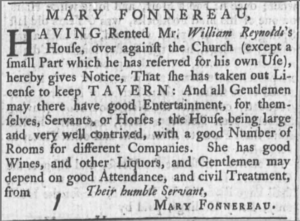

In 1747, this Church Circle building was leased by hatter, William Reynolds, who then rented it to Mary Fonnereau in 1755 who opened the tavern on the site. She advertised “good Wines, and other Liquors, and Gentlemen may depend on good Attendance, and civil Treatment.” Reserve a table for lunch, dinner, or an indulgent classic British afternoon tea, complete with sandwiches, cakes, and scones.

c. 1775 The Horse You Came in On Saloon, Baltimore

1626 Thames St., 21231; 410-327-8111

This Fell’s Point tavern, known by locals as The Horse, is the nation’s oldest continually operated tavern and is renowned for being the last place Edgar Allan Poe visited before his death.

c. 1785 Gadsby’s Tavern, Alexandria, Virginia

138 N. Royal St., Alexandria, VA 22314; 703-548-1288

The City of Alexandria operates both a restaurant and museum at this site. Try some of their historic dishes such as the Surrey Co. Peanut Soup, Meatloaf a la Daube, George Washington’s Favorite meal (duck and corn pudding), and Sally Lunn bread.

c. 1842 Casselman’s Bakery and Café, Grantsville

113 Main St., Grantsville, MD 21536; 301-895-5055

Established in 1842 by Solomon Sterner on the National Road to provide services for travelers, this restaurant is known for its soft yeast rolls and apple butter.

Let's keep in touch!

Keep up with the latest OutLook by the Bay information by signing up here. We promise not to waste your time.